Pennsylvania has a problem. A $2 billion problem.

From 2005 to 2015, I managed the plugging of nearly 1,000 wells in Pennsylvania, New York, and West Virginia. Many of the wells were old wells open to the atmosphere, leaking water, gas, or oil. My research indicated one firm had drilled tens of thousands of wells until the 1990s. Responsible companies like Shell Oil Company plugged many of the wells during my tenure after they learned they had acquired old wells through land transactions.

Many more wells were abandoned or orphaned for every responsibly plugged well.

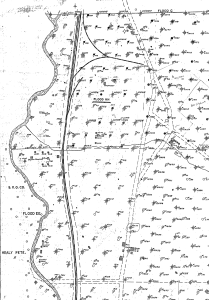

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PADEP) stated there are nearly 27,000 abandoned and orphaned wells on the state and private property. PADEP estimates it will cost $1.8 billion to plug the known wells. In addition, there may be as many as 200,000 unaccounted wells. Large and smaller operators abandoned many of these wells 50-100 years ago. By 1880, 4,000 wells were producing in the Bradford Oil District alone, yielding 50,000 barrels of oil daily. Oil City had 2,000 wells along the shores of the Allegheny River. In the 1940s, the Drake property near Bradford, Pennsylvania, had over 800 wells on 1,200 acres. Many of these wells had since been abandoned or orphaned.

The abandoned/orphaned wells present several potential problems: surface water contamination, groundwater, or drinking water; methane migration to water wells or basements; hazardous air pollutants and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; and open holes.

Why have so many operators abandoned their wells without plugging them? And why are wells not properly plugged? The answers are multifaceted.

Inadequate plugging. In the early days, regulation of the oil and gas industry was motivated by the need to protect the oil and gas resources and not the environment. Many wells before the 1950s were either not plugged or plugged with little cement. Often tree stumps, brush, wood, and rocks, with a sack of cement thrown in, were used to plug wells. Even wells plugged in the 1950s and 1960s are not adequately plugged. When cleaning out old wells, we found junk in the hole like a deer skull, tools, brush, wireline, and trash.

Inadequate plugging. In the early days, regulation of the oil and gas industry was motivated by the need to protect the oil and gas resources and not the environment. Many wells before the 1950s were either not plugged or plugged with little cement. Often tree stumps, brush, wood, and rocks, with a sack of cement thrown in, were used to plug wells. Even wells plugged in the 1950s and 1960s are not adequately plugged. When cleaning out old wells, we found junk in the hole like a deer skull, tools, brush, wireline, and trash.

Funding and Grant Programs

To address these environmental and safety issues, on November 15, 2021, the federal government enacted the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which allocated $4.7 billion to create a new federal program to address orphan wells. Nearly every state with documented orphaned wells submitted a Notice of Intent (NOI) indicating interest in applying for a formula grant to fund the proper closure and cleanup of orphaned wells and well sites.

Pennsylvania applied for and has received an initial grant of $25 million. The state applied for and received a Phase One Formula Grant of $79 million and is eligible for an additional $315 million Performance Grant in future years. The law also provides a separate $500 million program for the remediation of orphan wells on federal land, which the Department of the Interior (DOI) Bureau of Land Management will implement.

The DOI released draft Formula Grant Guidance to the states and the public on January 23.

Pennsylvania Act 136 of 2022 (Act of November 3, 2022, P.L. 1987, No. 136 Cl. 58 – OIL AND GAS) became effective January 3, 2023. This legislation amends Title 58 (Oil and Gas) of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes to provide a mechanism for using grant money. It provides $40,000 for every eligible orphan well plugged with a depth of 3,000 feet or less or the actual cost of the qualified well plugger to plug the well, whichever is less. The Statutes also provide $70,000 for every eligible orphan well plugged at a depth greater than 3,000 feet or the actual cost of plugging, whichever is less.

In the event the qualified well plugger encounters unusual technical difficulties due to the condition of an orphan well, the department may, at its discretion, amend the grant award to cover the additional cost, with adequate documentation of those unexpected additional costs, if it doesn’t exceed the amount of the grant for a specific orphan well.

Success in managing this pressing issue requires dedicated effort and expertise from environmental professionals, in addition to government funding, who consider these factors:

Ownership due diligence. Researching ownership through title and tax records.

Where there are challenges, there are opportunities.

The investments to plug and remediate abandoned and orphaned wells create jobs, advance economic growth, reduce hazards, and greatly reduce GHG emissions to meet carbon reduction goals.

The process requires close coordination between the state, geologists, environmental engineers, and drillers. All are benefactors, and beneficiaries, along with the general public and the environment.