Hear from SCS Engineers experts at the ninth Global Waste Management Symposium in Indian Wells, California, February 25-28, 2024. SCS is also is a Silver Sponsor of the conference.

The GWMS serves as a forum to discuss applied and fundamental research, case studies and policy analysis on solid waste and materials management. The community of researchers, engineers, designers, academicians, students, facility owners and operators, regulators and policymakers will participate.

Numerous SCS Engineers experts will be on hand to discuss your solid waste management challenges, and several are presenting at the symposium, including:

The Environmental Research & Education Foundation (EREF) is a strategic partner of the symposium.

Click here for schedule, registration, and other conference details

Hope to see you there!

On December 5, 2022, the EPA released a memo providing direction under the NPDES permitting program to empower states to address known or suspected discharges of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Note that the list of Applicable Industrial Direct Discharges (page 2, paragraph A.1) includes landfills. The memo cites state programs in Michigan and North Carolina that other states may want to replicate. These approaches and others could help reduce PFAS discharges by working with industries, and the monitoring information they collect, to develop facility-specific, technology-based effluent limits.

As stated in its memo, the EPA’s goal is to align wastewater and stormwater NPDES permits and pretreatment program implementation activities with the goals in EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap. The memo recommends that states use the most current sampling and analysis methods in their NPDES programs to identify known or suspected sources of PFAS and to take actions using their pretreatment and permitting authorities, such as imposing technology-based limits on sources of PFAS discharges.

The Agency hopes to obtain comprehensive information by monitoring the sources and quantities of PFAS discharges, informing other EPA efforts to address PFAS. The EPA will need this information since new technologies and treatments are in development but remain unproven to work successfully in specific industries.

Other proposed actions by the Agency include designating two PFAS as Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) hazardous substances and an order under EPA’s National PFAS Testing Strategy requiring companies to conduct PFAS testing and nationwide sampling for 29 PFAS in drinking water starting in 2023.

In a letter to Congress, SWANA and NWRA associations request that regulation under CERCLA for addressing PFAS contamination assign environmental cleanup liability to the industries that created the pollution in the first place. Both associations note that landfills and solid waste management, an essential public service, do not manufacture nor use PFAS. Therefore, the general public should not be burdened with CERCLA liability and costs associated with mitigating PFAS from groundwater, stormwater, and wastewater.

Resources:

On December 5, 2022, the EPA released a memo providing direction under the NPDES permitting program to empower states to address known or suspected discharges of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). The memo cites state programs in Michigan and North Carolina that other states may want to replicate. These approaches and others could help reduce PFAS discharges by working with industries, and the monitoring information they collect, to develop facility-specific, technology-based effluent limits.

As stated in its memo, the EPA’s goal is to align wastewater and stormwater NPDES permits and pretreatment program implementation activities with the goals in EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap. The memo recommends that states use the most current sampling and analysis methods in their NPDES programs to identify known or suspected sources of PFAS and to take actions using their pretreatment and permitting authorities, such as imposing technology-based limits on sources of PFAS discharges.

The Agency hopes to obtain comprehensive information by monitoring the sources and quantities of PFAS discharges, informing other EPA efforts to address PFAS. The EPA will need this information since new technologies and treatments are in development but remain unproven to work successfully in specific industries.

Other proposed actions by the Agency include designating two PFAS as Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) hazardous substances and an order under EPA’s National PFAS Testing Strategy requiring companies to conduct PFAS testing and nationwide sampling for 29 PFAS in drinking water starting in 2023.

In a letter to Congress, SWANA and NWRA associations request that regulation under CERCLA for addressing PFAS contamination assign environmental cleanup liability to the industries that created the pollution in the first place. Both associations note that landfills and solid waste management, an essential public service, do not manufacture nor use PFAS. Therefore, the general public should not be burdened with CERCLA liability and costs associated with mitigating PFAS from groundwater, stormwater, and wastewater.

Resources:

Of interest to industries concerned with wastewater ammonia treatment or landfill leachate ammonia treatment.

SCS Engineers publishes a new SCS Technical Bulletin entitled “Treatment of Ammonia in Wastewater and Leachate – Considerations and Technologies.”

Reducing the amount of ammonia in landfill leachate and other industrial wastewaters are often necessary to meet discharge standards. Proven wastewater treatment technologies can effectively reduce ammonia concentrations, but selecting the right technology requires careful consideration. This SCS Technical Bulletin provides background on ammonia in wastewater, and reviews factors to consider in selecting a treatment technology. The Bulletin includes a review of eight of the most common and effective treatment and disposal methods for wastewater with elevated ammonia or nitrogen.

Read or share the SCS Technical Bulletin here.

Explore SCS’s Liquids Management resources here.

In this blog, we discuss the basics of various wastewater treatment methods in use today including process design parameters, advantages, disadvantages, and costs. Some of the wastewater treatment methods are better suited to landfill leachate treatment than others. For example, the traditional activated sludge wastewater treatment technology, discussed in this article is not suitable for landfill leachates, but it has been modified and improved so that its close cousin – for example the membrane bioreactor (MBR) – is much better suited for landfill leachate treatment. The blog is intended for those who manage projects that include leachate treatment but who are not wastewater or process engineers. We start by grouping treatment systems into three basic categories; biological, physical and chemical. Our first blog in the series focuses on biological treatment.

The oldest treatment technology for sanitary wastewater, with the longest track record, is biological treatment. It is effective for treating the type of wastewater generated by humans because it uses naturally occurring microbes to reduce organics, ammonia and other naturally occurring impurities. The modern version of this time-honored biological treatment process (from the 1960s forward) is known as the basic activated sludge (BAS) process. This is the type of treatment that is used at large publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) and the same form of treatment can be used, on a smaller scale, for landfill leachate. The wastewater to be treated, whether it is sanitary wastewater or landfill leachate, contains organic compounds, nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) and naturally occurring microorganisms. When given the right balance of soluble food, temperature, and oxygen, the microorganism population can be increased rapidly. In multiplying their numbers, the microorganisms absorb some of the food sources (organics) in the wastewater for energy and convert that to new cell mass (through cell growth and reproduction), carbon dioxide (CO2), and water.

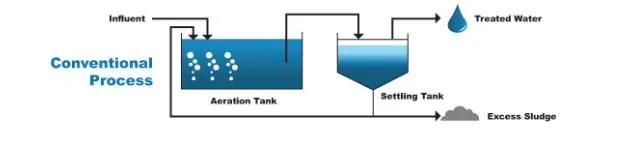

The actual BAS treatment process involves pumping the raw wastewater through an open tank, aerating and agitating the liquid by mechanically adding air or oxygen typically through a set of fine bubble diffusers, then after a prescribed time, passing that water to another tank called a clarifier. The process is illustrated below.

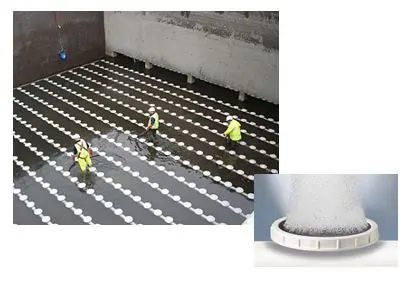

The dispersion pattern and the buoyancy of the bubbles promote mixing of the tank contents to ensure the bugs are getting adequate oxygen. An example of a bubble diffuser disc and a typical bubble diffuser bank layout is shown in the two photos below.

A process called nitrification also occurs in the aeration tank. Nitrification is a microbial process by which reduced nitrogen compounds (primarily ammonia) are sequentially oxidized to nitrite and nitrate by the species of microbes called Nitrosomonas, Nitrosospira, Nitrosococcus, and Nitrosolobus.

A biological system, such as a BAS has a susceptibility to some chemicals in leachate that in certain concentrations can be toxic to the “bugs.” For example, high concentrations of ammonia (NH3), chlorides or toxic substances can be harmful. Also, the treatment effectiveness of biological systems drops off significantly at a wastewater temperature lower than about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Rapid changes in concentrations of these chemicals (or spikes) also can be harmful.

In the clarifier, flocculation chemicals are added to the water to aggregate and help to settle out the cell mass. The cell mass, almost 99% water, is called sludge. Periodically some of the sludge from the clarifier is removed and brought to the front of the process where this “activated” sludge (i.e., air enriched and microbes are alive) is used to seed the incoming wastewater with robust microbial growth and boost the growth of existing organisms that break the organics down. The balance of sludge (called “biosolid”) is removed from the clarifier and is typically dried, disinfected through use of high pH material and or heat and is then used as a soil conditioner directly or as a fertilizer ingredient.

The laboratory measurement of the amount of oxygen that microorganisms use to convert the food to new cell mass is called the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5). The five day long BOD test was the earliest measure of the organic strength of wastewater and is a rough indication of how much energy (and relative cost) will be expended to treat the wastewater. Landfill leachate is typically considered a strong wastewater compared to municipal wastewater which is considered weak to moderate strength. Many municipal wastewaters are weak because they are heavily diluted with groundwater and infiltration of rainfall.

A key design parameter for any BAS process is the Mixed Liquor Suspended Solids (MLSS). The MLSS is the concentration of suspended solids in the aeration tank. The suspended solids are mostly the active microorganisms that do the work of decomposing the organic substances. The MLSS for a BAS is typically 4,000 to 6,000 mg/l.

Many other water chemistry aspects must be considered with the BAS process. However, these have not been included to simplify this explanation.

Over the decades the BAS process has been modified to address the many different types and strengths of wastewater, increase energy efficiency, reduce treatment times, improve resilience to shock loads, and pollutant removal effectiveness. You may have heard them called Sequencing Batch Reactor (SBR), or powdered activated carbon treatment (PACT). These are variations of the BAS process. Because landfill leachate is somewhat similar in chemical makeup to municipal wastewater, with typically higher chemical constituent concentrations, the landfill sector has successfully borrowed municipal treatment technology. An improvement to the BAS process that started showing up at landfills about 15 to 20 years ago is known as the Membrane Bio-Reactor (MBR) shown here.

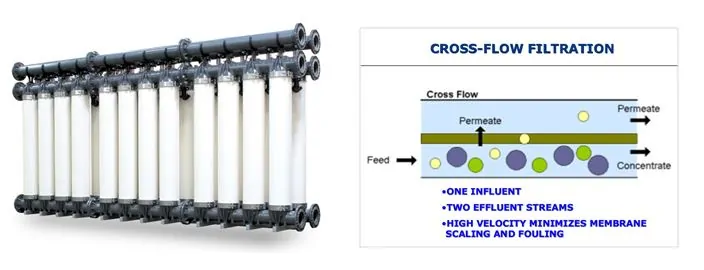

The MBR took advantage of advances in micro-manufacturing capability in perfecting synthetic membrane filtration fabric. The membrane, when incorporated in the treatment process, eliminates the need for a clarifier. The membrane works by separating insoluble solids from the water. The advantages of the membrane filtration include;

The membranes are manufactured either as a cylinder shown below-left, or as a flat plate used in a rack outside the BAS reactor, or immersed in the BAS reactor. The diagram shown on the right illustrates the membrane filter process.

Some disadvantages of the MBR can include:

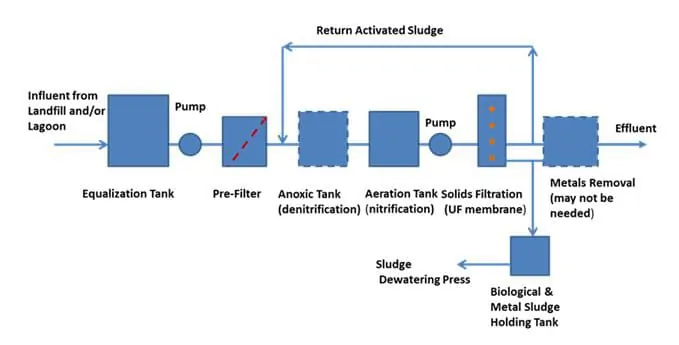

The MBR can manage a much higher MLSS than a conventional BAS; a typical maximum for a BAS is about 4,000 mg/l as compared to around 16,000 mg/l or more in an MBR. The higher MLSS allows for treating a stronger waste stream, and the system has better cold weather and shock load resistance. It can do this because the solids eventually are removed by a membrane. In the BAS process, the chemical treatment in the clarifier forms a large volume of sludge (organic chemicals + microorganisms) that has to be kept in balance by frequent sludge wasting out of the system. Without this wasting, the sludge volume recycled to the aerobic tank would overwhelm the aeration capacity, and the process would collapse. A process flow diagram may look like the one below.

Typically, landfill leachate may need other treatment processes to supplement an MBR system to meet requirements for reducing specific pollutants and other parameters before the treated effluent can be released to the receiving water. One of the key parameters is ammonia (NH3) nitrogen.

Ammonia is produced in the landfill by microorganisms utilizing the organic substances in waste for energy and reproduction in an anaerobic (without oxygen) environment. In an aerobic environment outside the landfill, ammonia can be oxidized by bacteria in a process called nitrification, converting ammonia to nitrite and then to nitrate. When combined with enough phosphorus, nitrates released to surface waters in high enough concentrations can promote algae blooms. The algae blooms typically die off from cold, or their normal lifespan. Large amounts of dead algae compete for oxygen with fish and other wildlife. The result can be fish kills, which can further worsen the water body oxygen depletion problem.

So, in addition to the ammonia being converted to nitrite and then nitrate, the nitrate-nitrogen typically must be removed before discharge of the treated wastewater effluent to surface water. The nitrite and nitrate removal process is known as denitrification and involves reducing the nitrate to nitrogen gas which is inert and not harmful to the environment. Denitrification in the leachate treatment process can be accomplished either by ion exchange, chemical reduction, or biological processes.

The biological method is very common and is typically conducted in a tank known as the anoxic tank. The anoxic tank typically has a filter bed containing the nitrate conversion microorganisms where the nitrate-laden water is passed through for treating. No air is added to maintain an environment that is suitable for the heterotrophic microorganisms that convert nitrate to nitrogen gas. Methanol or acetic acid is typically added to provide a food source for the denitrifying culture in the filters.

Some other key process parameters for the MBR that will affect process sizing and footprint includes the following:

For example, using these unit costs an MBR plant rated at 65,000 GPD would have a basic capital cost of $1.2 to $1.4 million. This does not include a building. The annual operating cost of chemicals and energy only (not including labor), with 90% availability would be $640K to $1.07 million. Extra costs would include; a building if desired or necessary, electrical supply, equalization tank, yard piping, bench and pilot tests, and engineering. These are rough figures to give the reader a sense of the magnitude of costs. Actual costs will differ. It is always best to check with one or more vendors on the unit costs they experience with installations that they provide.

Biological processes have been adapted successfully from the municipal wastewater industry by the wastewater equipment manufacturers who service the solid waste industry to treat landfill leachate. They form the basis of a viable treatment platform that can be expanded depending on the effluent requirements and other design goals. By coupling high-quality membrane filters to remove solids with the BAS-type treatment modifications, MBR plants are revolutionizing leachate treatment. MBR plants are a more efficient and more effective treatment of higher strength leachates. Many vendors are offering modular systems that fit well with the leachate production and growth typical at landfills.

In our next blog, we will discuss membrane filtration systems that are increasingly finding application where leachate has to meet tough discharge standards. Follow SCS Engineers on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.

Learn more about Liquids Management – Leachate Services

See you in Nashville! SCS Engineers

Landfill operators are seeking new means to dispose of leachate generated at their facilities more economically. Rising costs of leachate treatment at publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) obliges landfill operators to look for alternative disposal means at a lower price. These situations encourage landfill operators and consultants to do more with less when designing preventative solutions to reduce leachate generation in the first place.

Upstream measures to reduce leachate generation range from standard operating procedures to innovative ideas with significantly high benefit to cost ratios. SCS compiled a list of our Top 10 measures to consider, including:

1. Grading – Creating landfill plateaus to maximize rainwater runoff toward perimeter storm water ditches, using low permeable soil to seal landfill slopes that will not receive waste for an extended time.

2. Caps & Covers – Using temporary geomembrane caps over areas that will not receive waste for a long time. Constructing final cover over landfill final slopes to eliminate rainwater percolation into landfill.

3. Swales – Constructing temporary and strategic swales on landfill outside slopes to capture rainwater runoff before causing soil erosion on the slope and to convey runoff water to perimeter ditches.

4. Berms & Downchutes – Constructing temporary berms and swales on landfill slopes that drain toward new disposal cells to capture water before reaching waste in the new cell and directing water to perimeter ditches. Also, constructing a berm at the crest of slopes to minimize the flow of rainwater runoff over slopes that are causing soil erosion. Constructing engineered temporary and sturdy downchutes for rainwater runoff from top areas of the landfill to the perimeter ditches.

5. Tarps – Installing rain tarp over a portion of a new cell that will not be in service for some time.

6. Exposure – Minimizing exposure of the active face while the remaining areas are properly graded to shed rainwater runoff to perimeter ditches.

7. Shedding – Grading the top area of each lift to shed rainwater runoff to outside slopes and the perimeter ditches.

8. Plantings – Installing sod or seeding on exterior slopes and those interior slopes that will not receive waste for an extended time to reduce soil erosion.

9. Roads – Constructing ditches adjacent to access roads to safely convey runoff water to the bottom of the slope – pitching access roads toward the ditch adjacent to the road, and building a proper road surface to minimize erosion during severe storms while lasting long under traffic loading.

10. Maintenance – Establishing routine maintenance protocol for the aforementioned measures because regular maintenance sustains long life and performance.

For facilities outside the landfill area, special measures, such as using floating covers on leachate ponds or canopies over operations that could potentially generate leachate without the canopy, also help reduce leachate generation.

Upstream measures are not necessarily limited to our Top 10 list but depend on the type and extent of operations at a facility. The will of the landfill operator and the expertise of the solid waste engineer can go a long way to reducing leachate generation at landfill facilities, and we all strive for that.

More about Liquids Management including case studies.

Many landfill operators and owners are now spending more than 10 or 20 cents per gallon for leachate management, which can become quite costly. One of the primary reasons that leachate management has become an expensive challenge in the United States is more stringent regulatory policies regarding the discharge of liquids into public waters. The regulations affect publicly owned treatment works (POTW), which has led some POTWs to require that leachate entering their plants have adequate pre-treatment to remove contaminants. Under these circumstances, some landfills are forced to collect and haul their leachate to a different POTW or to consider installation of pre-treatment equipment themselves.

Each landfill needs a solution to its leachate management issues that depends on applicable regulatory restrictions, the capability of the local POTW, and the leachate composition. Due to chemical reactions and biological activity inside the landfill, the leachate’s temperature is frequently warmer than area groundwater. Also, leachate is odorous, and generally brown in color, with colloidal suspended solids. The composition of leachates depends on the composition of a landfill’s waste, the landfill’s decomposition stage, and weather conditions. Many factors are evaluated to arrive at an efficient and economical treatment method for disposal of landfill leachate.

There are some treatment alternatives available to reduce the high organic and nitrogen loads in leachate. For some leachate applications, the treatment methods are sufficient to allow the POTW to process the leachate safely. If treatment is not possible, or cost prohibitive another alternative is to pre-treat the leachate, lowering the contaminant load to prevent subsurface precipitation, and then dispose of it using deep well injection. Some states require little or no pre-treatment before discharging leachate to deep injection wells.

The following technologies are available for the pre-treatment of landfill leachate: biological processes for wastewater treatment such as membrane bioreactors, sequencing batch reactors, activated sludge processes plus reverse osmosis. Wet oxidation processes, activated carbon adsorption, as well as precipitation, coagulation, and flocculation techniques are also used, depending on the contaminants and their concentrations. These two counties are using a combination of treatment technologies for their leachate management strategies.

Hillsborough County’s 60,000 Gallon Per Day Leachate Treatment Facility at Southeast County Landfill

New Hanover County’s Landfill Leachate Treatment Plant Using Reverse Osmosis

Effective leachate management applies unique combinations of technologies which most adequately address the previously mentioned factors. To provide a truly sustainable solution to leachate management, SCS suggests another approach, which is to consider the landfill design and operations as part of the solution. By using the existing landfill design and operations, SCS develops an integrated approach to leachate management that is preventative. The benefits of using an integrated approach are that they are often a more cost-effective solution in the long-term, sustainable, working with the existing landfill’s infrastructure.

Waste Management is using an integrated approach at Monarch Hill Landfill in Pompano Beach, Florida. Monarch Hill Landfill is a 385-acre landfill with a waste flow of 5,000 tons per day. SCS helped decrease leachate formation as part of overall landfill design and operation. Waste Management reduced leachate formation using the following methods:

Temporary caps – SCS designed and provided monitoring services during installation of a 10-acre temporary geomembrane cap over a portion of the top intermediate plateau of the landfill. It reduced leachate generation, decreased odors, increased gas collection efficiencies, and addressed leachate seeps on the slope, as well as making surface water runoff over the top of the landfill easier and more efficient.

Final covers – SCS designed, permitted, and provided monitoring services during construction of six partial closure projects. The final covers were equipped with leachate toe drain systems below the final cover geomembrane, enabling leachate seeps to be collected and disposed of efficiently. The design also allowed collection of gas from the lower portion of the slope after completion.

Rainwater Toe Drain Systems – SCS designed a toe drain system above the final cover geomembrane that enabled water to be collected and diverted to the landfill perimeter ditches, preventing pore pressure build up and keeping the system stable.

Tack-on Swales – SCS designed tack-on swales that were implemented to catch runoff and convey water to downchute pipes. The swales could be easily adjusted based on the size of each partial closure and the overall management of stormwater.

Our approach is to develop a robust, tailored liquids management program comprised of the most appropriate technologies and engineering design to tackle the unique set of challenges facing each landfill client. In an era of doing more with less, clients find our programs are more cost-effective because they are more efficient and well designed.

Learn more at SCS Liquids Management

Contact one of our National Experts or service@scsengineers.com:

Darrin Dillah: Landfill Leachate – Upstream

Ron Wilks: Landfill Leachate – Downstream and Evaporators

Monte Markley: Deep Well Injection

Bob Speed: Dewatering

Ali Khatami: Landfill Engineering and Construction Impacts on Liquids Managment

Sam Cooke: Industrial Wastewater Treatment