A few years ago, an engineer working for a“friend’s plant” chose to replace their evaporative condenser with an adiabatic condenser. On the surface, the choice seemed like a good idea since adiabatic condensers often provide higher heat rejection with lower water and electricity usage. The condenser was purchased and installed, but all was not well. When not carefully considered, replacing equipment or control programs can have unforeseen consequences such as negative impacts on operational safety.

In this real life example the author examines what information would have made a big difference and significant savings had the right questions been asked.

Click to read this article and others written for those in industries using ammonia refrigeration.

Regulatory policies governing the food industry are in flux giving corporate compliance headaches, but it doesn’t need to keep you up at night with a massive workload. Consultants are an option if you lack the workforce or expertise to conduct PSM/RMP compliance audits.

William Lape, CIRO, reviews the questions to ask of your consultant before hiring. Starting with the amount of experience that the auditor has evaluating programs against the PSM/RMP regulations; review the resumes and auditor’s support structure; training related to the PSM/RMP regulations and how to properly audit; and ask questions, is the auditor familiar with your covered process, or just PSM/RMP in general? Imagine hiring a consultant with the lowest price and discovering s/he has little experience with ammonia refrigeration.

Read this article and others by clicking here.

The Georgia Manufacturing Alliance (GMA), based in Lawrenceville, GA, is a professional organization founded in 2008 to support Georgia’s manufacturing community. SCS Engineers is pleased to announce the firm is GMA’s newest member supporting manufacturers with permitting, compliance, and other environmental services.

Mike Fisher, SCS’s point of contact, has three decades of experience supporting environmental consulting for manufacturers and other industries throughout Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, the Bahamas, and South America. Mike has deep well petroleum geology expertise dating nearly four decades.

Learn more about each of our manufacturing solutions areas by clicking on the links below:

By Ali Khatami

MSW sanitary landfills constantly face the issue of aesthetics due to leachate seeping out of the landfill slopes. Of course, the problem goes away after the construction of the final cover, but the final cover construction may not take place for many years after seeps show up on slopes. To the public, leachate seeps represent a problem with the design of the landfill and possible malfunction of the leachate collection system below the waste, which is an incorrect perception. Such arguments are common and difficult to counter.

Landfill operators use different means to control leachate seeps from landfill slopes and to clean up the unpleasant view of the seep as soon as they can. Innovative solutions to address the issue have been observed and noted in the industry. The degree of effectiveness of the solution to some extent depends on the amount of money spent to address the problem. Some landfills are located in rural areas and the operator may not mind the unpleasant appearance of the slopes, so naturally no urgency in addressing the issue or no money available to take care of the problem.

The environmental side of the leachate seep issue is the impact to surface water quality. If leachate seeps remain unresolved, liquids coming out of slope may eventually reach the landfill perimeter and mix with stormwater in the landfill perimeter ditch. At that point, the operational issue turns into a compliance issue, and regulatory agencies get involved. If the public around the site is on top of their game concerning their opposition to the landfill, they can take the non-compliance issue and turn it into a political issue. At that point, the landfill operator finds himself or herself on the hot plate dealing with the agency and the public on an environmental impact matter.

It always makes sense to stay ahead of the issues and address any potentially sensitive condition before it turns into a major problem. As discussed above, addressing leachate seeps can be done in many different ways, and the operator needs to be prepared to fight for funds to address leachate seeps as they appear on slopes. Availability of funds and willingness of the operator to take necessary action are the primary required elements to stay ahead of the game.

SCS has developed methodologies to address all sorts of leachate seeps on landfill slopes and is uniquely equipped to assist you with a solution. Reach out to a local SCS office for a consultation if you have leachate seep problem at your site.

This paper, presented at A&WMA’s 111th Annual Conference details the Tier 4 process and the potential issues that have arisen from conducting a Tier 4. This paper also assesses potential Tier 4 sites, exceedance reporting, wind monitoring, additional SEM equipment requirements, penetration monitoring, notification and reporting requirements, and impacts on solid waste landfills that will use the Tier 4 SEM procedure for delaying GCCS requirements. This paper reviews the changes between the draft NSPS and the final version of the new NSPS that was promulgated.

Click to read or share the paper, and learn about the authors.

SCS Engineers continues to expand and advance its team of environmental professionals in Northern California by welcoming Wendell L. Minshew, a licensed professional engineer specializing in civil engineering.

“As a highly-qualified addition to the team, Wendell will help SCS Engineers provide exceptional environmental service to our clients in Northern California,” said Ambrose McCready, Vice President with SCS Engineers. “His significant background in engineering strengthens our regional team, and helps ensure we meet and exceed client objectives.”

With more than 30 years of engineering experience, Minshew specializes in leading the design, planning, permitting and construction management of solid and hazardous waste facilities. He obtained his Bachelor of Science in civil engineering from CSU Fresno and is a licensed Professional Engineer in California, Nevada, Oregon, and Arizona.

SCS serves Northern California through our offices in the San Francisco Peninsula, Sacramento, Oakland, Modesto, Santa Rosa, and Pleasanton. See our nationwide locations.

Duluth, GA – SCS Engineers, a leader in environmental and solid waste engineering, recently relocated from Alpharetta to a larger, more strategically located office in Duluth, Georgia. The new office supports SCS’s continued development in the Southeast, our client success-driven growth, and accommodates our growing professional staff.

SCS is always on the lookout for talented senior level professionals in the environmental consulting community. The Atlanta Environmental Services (ES) group is seeking experienced, humble, hungry, and smart senior level consultants with client relationships and business development capabilities to join our team.

SCS Engineers – Atlanta

3175 Satellite Blvd

Building 600, Suite 100

Duluth, GA 30096

(678) 319-9849

If you are interested or know anybody who is interested, reach out to . You may also review our open positions on the SCS Careers Page.

SCS Engineers welcomes Steven J. Liggins as Vice President and Controller. Steve, a certified public accountant, joins SCS with over ten years of experience in related financial positions with service driven companies. As the accounting officer at SCS, Steve is responsible for ensuring effective and efficient recording of accounting transactions, as well as monitoring adherence to established operating procedures and internal controls.

“Steve not only knows our business and our clients’ industries, but he brings valuable tax expertise, which is increasingly important,” stated Curtis Jang, CFO at SCS Engineers.

Steve has an MST in Taxation from Golden Gate University as well as a BA in Business Management and Accounting from Western Michigan University, Haworth College of Business.

Deep injection wells (DIW) mean different things in different parts of the country. In the midwest DIWs have been used for decades to dispose of industrial wastewaters, mining effluent, and produced water from oil and gas production activities and are from 3,500 feet to more than 10,000 feet deep. In Florida, deep injection wells have been used since the 1960s; however, they are used to dispose of treated municipal wastewater, unrecyclable farm effluent, and in some cases landfill leachate. DIWs in Florida range from 1,000 feet to around 4,500 feet deep.

This is a two-part blog, the first part discussing what constitutes a DIW, their general features, their cost relative to other wastewater management alternatives, and the range of industrial wastewaters suitable and safe for disposal. The second part, covered in the next SCS Environment issue, will be on the challenges for deep well developers created by public and environmental organizations, and strategies to counter misinformation and means to obtain consensus from stakeholders.

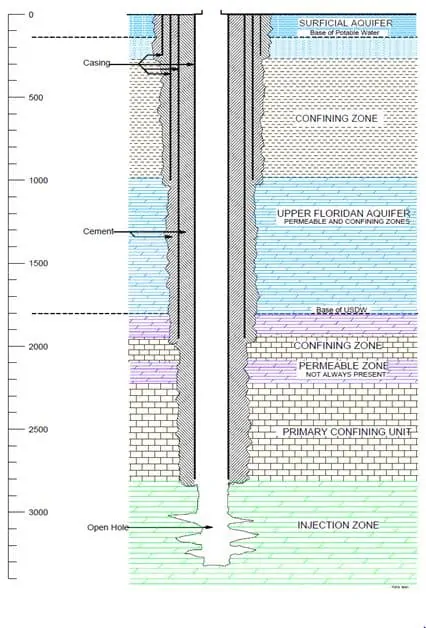

A DIW construction is a series of casings set in the ground where the initial casing starts out large and subsequent casings become smaller in diameter, progressively telescoping downward. Casing materials are typically steel alloys or fiberglass for better chemical resistance. As a casing is set and rock is drilled out, the next casing is set and cemented with a chemically resistant grout. The process continues with each progressively deeper casing. These redundant “seals” are what keep the injected liquid from escaping into the protected aquifers.

A DIW typically has three upper casings to protect the aquifers and isolate the wastewater to the desired disposal zone. The inner casing, called the injection tube, extends to the injection zone. Mechanical packers seal the space between the injection tube and the last casing with the annular. The resulting annular space is filled with a non-corrosive fluid. This fluid is put under pressure to demonstrate the continuous mechanical integrity of the well. The annulus is monitored for potential leaks, which would register as a loss in pressure and promptly stop the injection. Figure 1 is a simplified view of a DIW casing system used in south Florida.

Vertical turbine pumps working in conjunction with a holding tank, which is a used to smooth out the fluctuating flow of the wastewater feed pumps, propel the liquid down the well. As part of the permitting efforts, a chemical compatibility study is conducted to determine the level of pre-treatment if any to protect the well components and minimize downhole plugging. Municipal wastewater effluent is regulated differently and must receive at least secondary treatment before injection.

In the Midwest, DIWs are constructed to the same EPA criteria with a wide range of operating conditions. Some wells take fluid under gravity with no pumping, while others require higher pressure pumps that exceed 2,500 psi for injection. This blog focuses on wells used in Florida and typical fluid types and operational parameters.

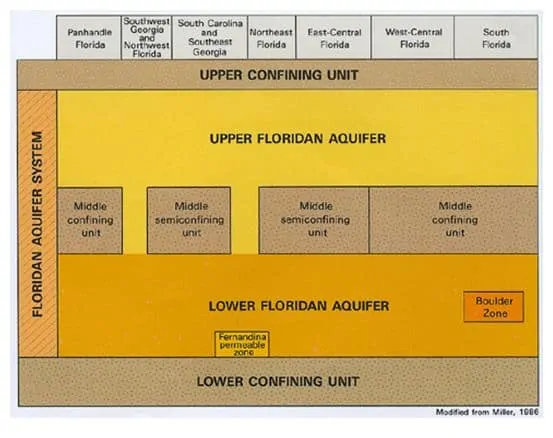

In central and south Florida the injection zone lies below the underground sources of drinking water (USDW) which is the depth at which water with a total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration exceeds 10,000 parts per million (ppm); or the “10,000 ppm line”. This water is considered to be unusable in the future as a drinking water source. In parts of Florida, the injection zone is dolomite overlain by a series of confining units up to 1,000 feet thick made up principally of limestone with permeability several orders of magnitude less than the injection zone. (1)

In central and south Florida the target injection interval is the “Boulder Zone,” reportedly named because drilling into the formation often broke off pieces of the formation and made drilling difficult. The Boulder Zone is also known as the lower portion of the Floridan Aquifer. Later down-hole imaging technologies revealed this zone to be characterized by highly fractured bedrock and large karstic caverns, and the ability to inject relatively high flow rates with relatively little backpressure. It is not uncommon for Florida DIWs to have well flow rates exceeding 15 million gallons per day (MGD) and backpressures ranging from 30 up to 100 pounds per square inch (psi).

The versatility of the DIW in Florida to accommodate numerous different types of wastewater is an advantage. DIWs are being used on a large variety of waste streams that continues to expand, including:

Any wastewater considered for disposal must be compatible with the target formation and the final casing material. Therefore, depending on the wastewater, it may be straightforward to use existing industry references to confirm compatibility. In some cases, laboratory bench tests may be necessary to confirm compatibility.

Compatibility also includes the potential for creating unwanted microbial growth and scale formation within the injection interval. Growth and scale can happen with effluent containing sulfur or ammonia, two food sources for microorganisms or wastewaters supersaturated with minerals. Unless planned for and evaluated properly, both of these items have the potential to grow and clog the formation around the well, significantly reducing flow and increasing back pressure. This can result in higher energy costs, regulatory action and significant, unplanned costs to rehabilitate the well.

Another significant aspect of municipal wastewater is that they are primarily composed of freshwater and thus when injected into the highly saline Boulder Zone or similar saline zones, will tend to have a vertical migration component because of the density difference and greater buoyancy than the target zone. A few wells have been taken out of service because the seals designed to prevent this migration failed and allowed wastewater to seep upwards into the USDW.

The US EPA Underground Injection Control (UIC) program is designed with one goal: protect the nation’s aquifers and the USDW. There are several protective measures in a DIW that are intended to meet this objective;

The U.S. EPA conducted a study in 1989-1991 of health risks comparing other common and proven disposal technologies to deep wells injecting hazardous waste. The U.S. EPA concluded that the current practice of deep well injection is both safe and effective, and poses an acceptably low risk to the environment. In 2000 and 2001 other studies by the University of Miami and U.S. EPA, respectively, suggested that injection wells had the least potential for impact on human health when compared to ocean outfalls and surface discharges(3). William R. Rish examined seven potential well failure scenarios to calculate the probabilistic risk of such events.These scenarios included four types of mechanical failures, two breaches of the confining units, and the accidental withdrawal of wastes. The overall risk was quantified by Rish as from 1 in 1 million (10-6) to 1 in 100 million (10-8) (4), which is no greater than the current EPA risk criteria for determining carcinogen risk. As a comparison, 10-6 is the same risk level used by EPA for contaminants in soil or groundwater that are a known carcinogen.

There are several studies in Florida conducted by researchers and practitioners in the deep injection well field to assess the actual potential for municipal wells to contaminate the USDW. The maximum identified risk associated with injection well disposal of wastewater in south Florida is the potential migration of wastewater to aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) wells in the vicinity of injection wells (Bloetscher and Englehardt 2003; Bloetscher et al. 2005).

In a 2007 study, 17 deep wells in south Florida, used for municipal waste disposal, that had known upward migration into the USDW, were evaluated to develop a computer model to simulate these phenomena and extrapolate vertical migration over longer time periods. The results indicated that the measured vertical hydraulic conductivities of the rock matrix would allow for only minimal vertical migration. Even where vertical migration was rapid, the documented transit times are likely long enough for the inactivation of pathogenic microorganisms (5).

In a 2005 study of 90 South Florida deep injection wells, the authors took actual field data and constructed a computer model calibrated to actual operating conditions. The intent was to model performance of two injection wells in the City of Hollywood, Florida that the authors were familiar with and to determine the likelihood of migration, and what might stop that migration. Density differential and diffusion were likely causes of any migration. No migration was noted in Hollywood’s wells. The preliminary results indicate that Class I wells can be modeled and that migration of injectate upward would be noticed relatively quickly (3).

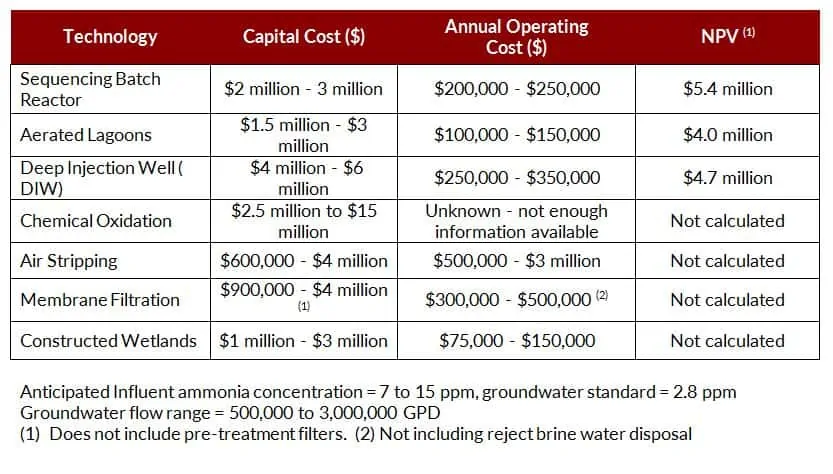

A deep injection well lifecycle cost compares favorably with other traditional waste treatment and disposal techniques. A life-cycle cost includes the capital cost and operating and maintenance costs for the useful life of the system. On a recent project, the wastewater for disposal was groundwater contaminated with ammonia nitrogen from a former landfill. The estimated groundwater recovery rate and the deep injection well disposal rate was calculated to be 1.2 million gallons per day (MGD). The proposed deep well was designed to have a final casing of 12-inch diameter, an 8-inch diameter injection tubing to a depth of 2,950 feet, and below that approximately 550 feet of open bore hole. The lifecycle cost estimate comparison to other viable technologies is shown in the Table below.

In this case, there were no projected revenues, so the alternative with the lowest net present value (NPV) would technically be the preferred alternative. Even though the aerated lagoon had the lowest NPV, it was ultimately judged too risky with a long break-in treatment period and significantly more space for treatment ponds needed.

The increasingly stringent surface water discharge standards are an ongoing challenge for industries generating a wastewater stream. DIW’s should be considered as a potentially viable option for long-term, cost-effective wastewater disposal, where a viable receiving geologic strata exists and when wastewater management alternatives are evaluated. In Florida, they currently provide an environmentally sound disposal option for many regions.

Within the SCS Engineers’ website, you will find the environmental services we offer and the business sectors where we offer our services. Each web page offers information to help you qualify SCS Engineers and SCS’s professionals by scientific and engineering discipline.

We provide direct access to our professional staff with whom you may confidentially discuss a particular environmental challenge or goal. Our professional staff work in partnership with our clients as teams. We are located according to our knowledge of regional and local geography, regulatory policies and industrial or scientific specialty.

The industry standard SP001 is incorporated into many Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) Plans is now updated. How does it affect your facility’s SPCC Plan?

The Steel Tank Institute (STI) recently released an updated version of SP001 – Standard for the Inspection of Aboveground Storage Tanks. This document is the industry standard used in most SPCC Plans for inspection guidelines and integrity testing for shop-fabricated aboveground storage tanks. In a typical SPCC Plan prepared by SCS Engineers, your monthly and annual inspection forms, and tank integrity testing frequency requirements are based on the criteria provided in SP001.

No. We recommend incorporating the updated inspection forms during your next SPCC Plan Amendment or 5-year renewal.

The inspection criteria have been simplified, and more flexibility is allowed with the revised inspection forms. This will help make your inspection process easier and of higher quality.

Need help sorting out the details of the revised standard, or have an SPCC Plan that needs amending or is due for a 5-year review? Contact , and we will help you stay on top of your SPCC needs with offices nationwide.

Coauthors: Denise Wessels and Amber Fidler.

SCS Engineers SPCC specialists in Pennsylvania.